Ignore these native advertising rules and regulations at your peril

Native ads have been around for a while, although they have gone by many other names in the history of media over the centuries. The legal concerns that come with them have been around just as long, too.

During the Federal Trade Commission’s workshop “Blurred Lines: Advertising or Content?,” attorney Lesley Fair stepped to the podium and announced “an FTC law enforcement action … a settlement in the area of native advertising,” as she called it, to a crowd of representatives from the largest publishers and agencies in the country.

As the likes of BuzzFeed and the Interactive Advertising Bureau nervously awaited the latest twist in the tale of native, Fair proceeded to describe a case from 1917 involving the Muenzen Specialty Company and its groundbreaking electric vacuum cleaner. The FTC decided Muenzen was deceiving readers with an ad disguised as “independent content,” she said, and invoked Section 5 of the 1914 FTC Act to stop them.

The language of Section 5 is quite simple:

Unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce are hereby declared unlawful.

And even when the FTC later elaborated on Section 5 with the “Deception Policy,” the spirit of the law remained intact:

When the first contact between the seller and the buyer occurs through a deceptive practice, the law may be violated, even if the truth is subsequently made known to the purchaser.

With Section 5 and the Deception Policy as guides, Fair then traced the evolution of native advertising, with the ultimate point being: No matter how it’s packaged or where and when it’s running, the FTC has historically kept a close eye on advertising every step of the way. And if you’re going to push the envelope, that envelope had better be clearly marked.

This isn’t to alarm you, nor is it to imply that native ads aren’t a wonderful tool for publishers and advertisers alike – when done right, they can be. But in striking a balance among sponsor, editor, and reader comfort levels, publishers must also consider the comfort of the FTC, despite the fact that it’s far from developing a universal enforcement system, let alone over-regulating native ads.

Indeed, the Blurred Lines workshop seemed to put forth more questions than answers about best practices when it comes to brand involvement, design principles, and disclosure language. But some common sense, self-governance, and checks and balances can be exercised.

IAB, with its “Native Advertising Playbook,” and Condé Nast with Tom Wallace’s recent manifesto, are doing just that.

First and foremost, readers aren’t stupid, but even geniuses can be deceived. It’s of paramount importance to establish a line between your advertising and editorial.

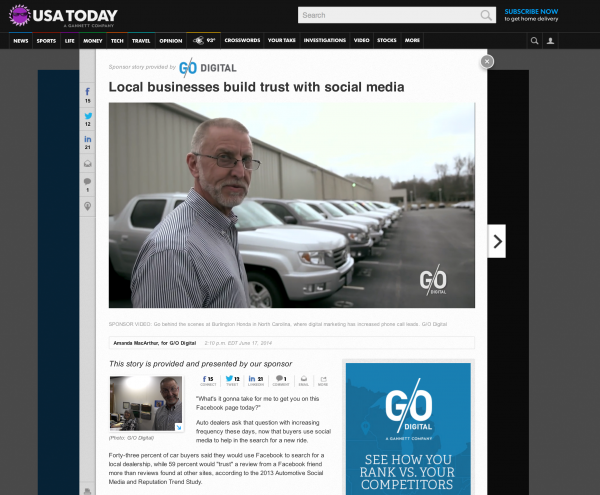

In this example on USA Today, which we’ve used many times because it’s so well structured, the news article is being sponsored by G/O Digital, and it’s clearly stated at the top of the article, in the byline and at the beginning of the article. G/O Digital also receives a banner ad on the article itself.

At the bottom of the article, there is yet another clarification that the article is sponsored.

One gauge the FTC uses to gauge whether an ad meets their standards is the immediate “net impression” on consumers. Though its formula is known only to the agency’s attorneys, we can come up with an approximation: If a reader looks at an ad on a magazine’s portal and initially believes it to be independent editorial content without a commercial agenda, you are inching closer to what the FTC terms a “masquer-ad” … and, in turn, potentially approaching illegality. In the example above, there is no question for the reader whether this content is sponsored.

Another red flag for the FTC is when they determine an advertiser is perpetrating a Body Snatcher trick and siphoning off some of the publisher’s integrity, quality control, and ethical standards with a lookalike ad. Of course, the publisher is likely not an unwitting victim in this scenario, but the onus is on the advertiser to craft “honest copy,” as it were.

In addition, the Specialized Information Publishers Association circulated a memo to members from the organization’s counsel, Levine Sullivan Kock & Schulz, LLP, that forecast a renewed scrutiny of native ads from the FTC.

For example:

-

“Particularly important for publishers, the [FTC] guides now provide that advertising examples of success stories must also disclose the results that most consumers can reasonably expect, if the advertised success story is not provably typical.”

-

“The safe harbor of the ‘results not typical, results may vary’ disclaimer no longer exists. Also, any ‘material connection’ you have with a company being discussed in a native ad must be disclosed.”

Are there any rules you’re confused about, when it comes to native advertising? Let’s discuss in the comments.

Any legitimate publisher with an established brand–who has spent years nurturing a relationship with their audience–would be foolish to try to trick their audience with any strategy or tactic that mis-represents sponsored content as editorial. Native presentation of clearly marked sponsored content can be very effective while maintaining the trust of the audience. And sponsors need to be sure to create sponsored content that is compelling; something that provides value to the audience.